Russell Banks

Member Spotlight - February 2020

Where did you grow up, and where do you live now? I was raised in Abilene, Texas (Think “Friday Night Lights.” The high school football stadium seated more than 20,000 in the 1960s!) I continued growing up in the photojournalism program at UT Austin. After 11 years in El Paso, and nearly 30 years in Portland, Oregon, we moved to a little town in northern Colorado where I live now.

Why did you join TPS, and how long have you been involved? I was a member of the Austin Photographic Cooperative Society (which later became TPS) in the early '80s, but drifted away from the organization, and photography, until recently. I rejoined TPS in 2019 at the urging of my long-time friend and former teacher at UT, Frank Armstrong.

Why did you become a photographer, and where do you find inspiration or motivation for your work? My interest began as a child with a Brownie Bullet and grew with a high school course. Photography came naturally and I wanted to get better, taking that interest to UT where I started as an English major, but soon switched to journalism, where I could take more photo classes. The writing and communications disciplines of the journalism department also fit me well. Of course, I'm still "becoming" a photographer!

I get motivated every day when I wake up and realize that there’s just one less day I have on this earth to make things. I love the feeling of looking at something wonderful and thinking, “I made that," while at the same time not really knowing how it happened. I’m inspired by people who work harder than I do.

How would you describe your photography and/or working process? When I'm out shooting, I’m a hunter-gatherer, waiting for a moment to happen or a promising scene to come into view as I move around. I’m just reacting to what I see and gathering raw material to take back to the studio. It starts out as documentary photography, but back in my studio, just about anything goes.

I use Adobe Lightroom to review, cull and catalog the images, and to do the initial camera raw editing before they go into Photoshop, where everything else happens. I usually don't know if I’ve captured anything worthwhile until weeks or months later. The first cut is always depressing, where I toss out about 80 percent of the shots as obvious failures. I put those in a “hold one year” folder in case I later find I need something from one of those files. I then wrestle with the remaining 20 percent: is there anything really good here? Am I repeating myself? Have I worked too close to the edge and slipped into the abyss?

Once I’ve chosen a promising image, I dive into Photoshop and work for hours with adjustment layers, masks, the Nik Viveza tool and even some content editing. I often modify hue and saturation of certain colors to strengthen the overall effect. It’s an iterative process, because making one adjustment often reveals another that needs to be made.

Then I make a proof print on Epson Luster paper, put it on my viewing shelf and live with it a while. Ultimately, it goes on Canson Infinity Baryta Photographique paper. I love its weight and smooth surface, like the old Ilford Gallerie silver paper dried face-down on window screens. For me, it's all about the print, because seeing a good print is a much better experience than viewing it on a screen.

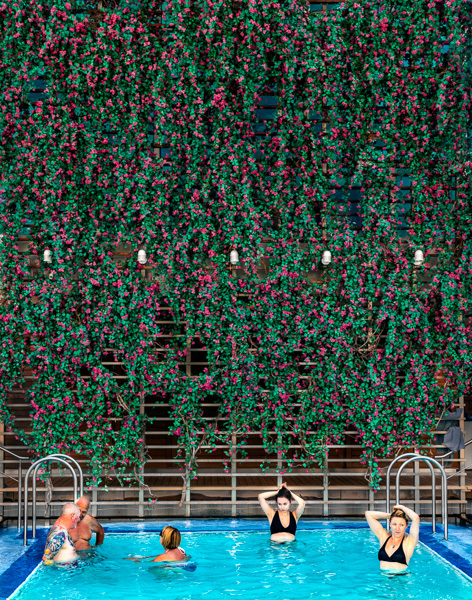

Please tell us about your most recent photographic work. Currently, I'm working on my “Floating World" project, exploring the complex social, economic and visual environment of today's behemoth cruise ships. For the passengers, it's a carefully managed experience, offering endless opportunity for indulgence. For the crew, it's a six-day work week of 12-hour shifts, with some sending their earnings back to family in less-advantaged places like the Philippines or Indonesia. For the corporations that own the ships, it's a chance to reap the benefits of cheap, unorganized labor and guests with the cash (or credit) for the "trip of a lifetime.”

Cruise ships present a challenging environment for shooting, with wind, vibrations, heat and lens-fogging humidity. There’s clutter and harsh light on the decks, while lighting is very dim inside the ship. Passengers and crew roam about in the background. There’s also the need to be discrete, since the cruise lines don’t allow activity they deem “commercial,” tightly controlling activity on their ships and the image they would want portrayed. Their authority on the high seas is nearly absolute and they do put passengers ashore that cause disruptions or disobey rules—usually with good cause.

I’ve been shooed-away from an art auction, had passengers complain to staff I was photographing them, and even had a security officer demand I delete a shot I made in an area they required passengers to transit as they exited the ship. (I fumbled about and convinced him I’d removed it, only later to actually delete it when I decided it was of no use.) The portfolio’s up to about 30 prints, and I’m still exploring subject matter and approaches.