Harvey Stein

Member Spotlight - September 2020

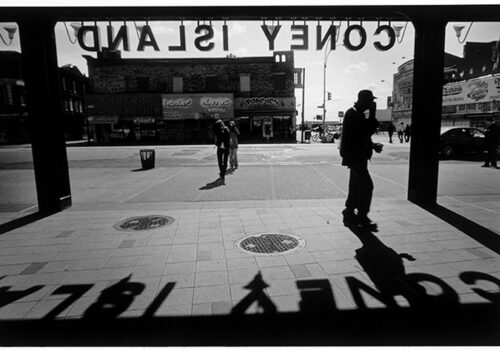

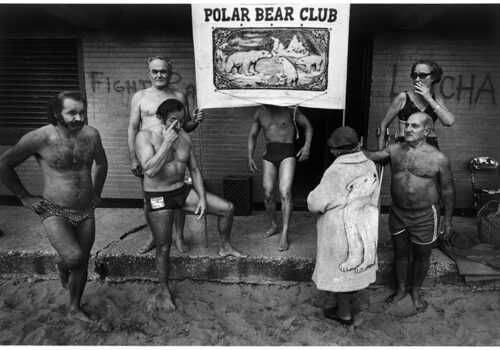

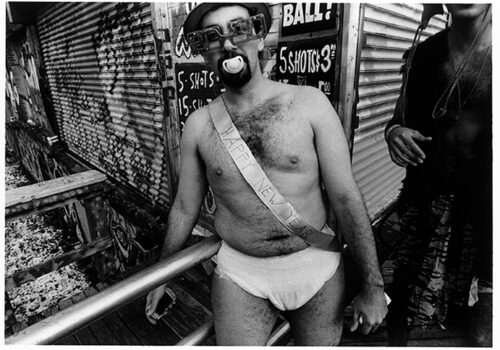

All Coney Island Images © Harvey Stein 2011

All Mardi Gras Images © Harvey Stein 2020

- Tell us about yourself. Why did you become a photographer?

I'm from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I lived there until I was 21 years old. I attended Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh and was introduced to art and theater for the first time. I got the bug to be more creative; however, I was studying engineering. I knew engineering wasn't for me but I couldn't switch gears at that time. I graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Metallurgical Engineering. After a year of working as an engineer, I served two years in the Army, based in Germany. It was there that I picked up a camera for the first time. I knew immediately that this was something I liked, and could do. The camera provided a way to express myself. Living in Europe also gave me a taste for international travel.

However, when I returned to the states I attended Columbia University's Columbia Business School in New York City and got an MBA. Again, the corporate world wasn't feeding my creative juices. During the weekends I pursued various photography projects around New York. In 1978 I completed my first photo book on identical twins, called Parallels: A Look at Twins and it sold 10,000 copies. It gave me the confidence to launch a full time photography career, so in 1979 I quit corporate work for good. I also started teaching at the International Center for Photography. I have taught for over 40 years now. I love teaching but I love photography more...

When I became a full time photographer, I supplemented my income with caption writing, magazine assignments, stock photography and teaching. A second book in 1986 generated additional revenue. I didn't have a studio although I set up a small darkroom and used my kitchen table to do much of the work. I kept my expenses quite low. I wasn't living elegantly but I didn't need a lot and it worked out pretty well. Later I started having shows and selling prints.

Since going full time, I've tried not to work in anything other than photography. This is my calling, my passion; it's what I do. I've never wanted to make films or do video. I am never bored because every day is different. I've gotten a bit discouraged at times but I keep bouncing back. I can't imagine ever stopping. Photography keeps me alive and energized and connected.

- Why did you join TPS?

I have been affiliated with and supportive of Texas Photographic Society since I taught a TPS workshop in Austin in the 1990's through D. Clarke Evans (TPS President Emeritus). TPS has been around a long time and has an active photographic community. I joined because of the great things the organization does for photographers.

- Tell us more about your photography. What do you specialize in?

I primarily shoot film. I develop my film at home and make prints, because I don't trust anyone else. I want to have control over the process. It is exhausting - once a week I go into the darkroom at nine in the morning and come out at nine at night - but it's a good day when I am realizing my vision in the form of prints.

In 2007 I got my first digital camera, but I don't particularly like digital and I am not that great at it. But I use it to shoot color, especially when I travel to India - I love the color there.

My main thrust is black and white. I love the dark and deep tones, its mystery. Black and white emphasizes the content and subject matter. I find it more personal and meaningful. I think we can get lost in the color. Color can distract you. I've seen wonderful color work that I admire greatly. But for me color takes away what I want to say. Black and white is important to me - it is my history.

I photograph with Leica film cameras that I've had for years. Shooting with black and white film is much more laborious than digital. I am usually about two years behind in processing my film. First you have to develop the film, then make the contact sheets, then make the prints. With digital you have the results right away. But I don't have the patience for using Photoshop and Lightroom. There's something to be said for the anticipation and the experience of making that image through film.

I call myself a street photographer and a portrait photographer. I've done landscapes and I enjoy them. However, I like a challenge. I like to go up to a person never knowing what is going to happen. If I photograph a bush or flower, there is no response. I want a reaction. I want to be acknowledged as a living, breathing individual. So I photograph social behavior in spaces that are conducive to that, like the street, or Coney Island.

I use a 21mm lens because it gives a sense of space and the environment. It allows me to get close to my subject and still incorporate a background to help tell the story. I want to show people and how they act and behave. I am endlessly fascinated by people. I am looking for that distinctive characteristic. In some ways street photography is easier. Since I am in New York City, I can roll out of my apartment, walk the streets and find amazing subject matter. Even now, during the pandemic, I am still photographing people in my neighborhood. They are all wearing masks but I am getting good images. People continuously surprise me.

- Where or from whom do you find inspiration or motivation for your work? Do you have a mentor?

I have always been independent and did not want to be influenced too much. My philosophy is you have to learn how to do it your way and on your own. I don't want to play into any movement or marketplace. I probably could have sold a lot more images if I were a little more commercial. I just want to be natural, real, authentic.

My first teacher in 1970, Ben Fernandez, was a rough, tough East Harlem guy and a loud, aggressive street photographer. He was my only mentor. He took me under his wing. I could be very shy and he taught me how to be bold - now I approach people left and right. Although Ben and I were very different from each other, we got along really well. I went to his house a lot and he allowed me to use his darkroom. He was the one who told me to get a Leica and go to Coney Island; I have been photographing there ever since. At one point, Ben said, "Look, you're getting too good," and he kicked me out. We stayed friends.

I like Garry Winogrand's work. He's my favorite street photographer. I relate to him because he was always behind in his film developing, as am I. When he died he left about 2,500 rolls of film undeveloped. I think to myself, "Wow, I am not going to be that extreme," but I have hundreds of rolls of film that I can't keep up with.

- You have done so many projects. What are you working on currently? What are you most proud of?

I prefer to do my own projects, many over a long period of time. It allows me to build consistent, coherent work on a theme in great depth. I've become an expert in some areas because I've researched, interviewed and photographed so much. I have several projects that I am working on and have published nine books, including two books on Coney Island. A third book, Coney Island People: 50 years, will be published in 2022.

Coney Island is iconic and historic. It is open all year in the sense that there's a beach and a boardwalk. There is also the amusement park which is seasonal. I go approximately 12 times a year, even in the winter. I've probably been there a thousand times. This is my 50th year of shooting on Coney Island, so I guess I am most proud of this work. It seems like I've spent all this time and effort on one subject, but it is really multiple subjects because the people are completely different. It is the same, yet it's never the same. I say, "You either have to be crazy or a genius to do one project for 50 years." I know I'm not a genius, so I must be crazy.

I love the work I did in the 70's on identical twins from birth to death - the sequence is perfect. I also spent five years in the 90's photographing people living with AIDS. I offered my services free of charge and I contributed photographs to support the Gay Men's Health Crisis.

In the late 70's and early 80's I went to Mardi Gras a few times with friends. We hung out together and shot together. The event was huge, crazy and strange. I shot with my film camera during the day but the film was too slow when it got dark. So I used my Polaroid SX-70 Instant Camera starting around twilight - photographing people up close in their masks and face paintings. I took about 60 photographs with the Polaroid, brought them home, stuck them in a drawer and did nothing with them. Recently a publisher asked if I had any work lying around that might surprise people, knowing it came from me, and I said, "Yes, this body of work from Mardi Gras." He saw the collection of Polaroids, liked them and is publishing a book. Then and There: Mardi Gras 1979 will be released at the end of September 2020 by Zatara Press. To purchase the book, go here.

- What's on your bucket list to capture?

There are still places I want to go including some countries in Asia and South America. Burning Man would be fun to go to. I would enjoy any place weird, not sophisticated or gentrified.

- Do you consider yourself a mentor to others?

Yes, I am a mentor to many, many people and students. I get this all the time: "You've changed my life, you've made my life better." Teaching is an important part of what I do, helping people understand photography, and giving back. It is very rewarding. If I had all the money in the world and I didn't have to teach, I would still teach. I learn as much from my students as they learn from me. I run into former students and we often reminisce about the class or experience. It's a nice feeling to know that my instruction was worthwhile and resonated.

- Any tips or advice for aspiring photographers?

Be patient and work hard. Practice every day. Find a project to work on and shoot what you like. If you don't know, then shoot everything at first - dogs, trees, buildings, people, your family. Eventually you will keep going back to the same subject matter. Be curious. And if you stop shooting, that's okay. Just be a fan of the art of photography.