By D. Clarke Evans

We are delighted to post this special interview with one of our very own colleagues, D. Clarke Evans, who served as the TPS president for twenty years, retiring in 2013. Over the past few years Clarke has dedicated his time to two photographic projects honoring military servicemen and servicewomen. We asked Clarke to share some insight about his series, "Before They're Gone: Portraits & Stories of World War II Veterans."

What drew you to, or was the inspiration for, this project?

It was Lieutenant Colonel Richard E. Cole's story which changed the course of my life. We met in 2015 at one of the first Monday of the month breakfasts I attend where we honor World War II veterans. I started attending these breakfasts several years ago when I began photographing and interviewing U.S. Marines. However, I had little time to fully pursue the project as I was the team photographer for the San Antonio Spurs.

Cole, a member of the U.S. Army Air Corps, was a genuine American hero—one of Tom Brokaw's "Greatest Generation." When Cole (in his 90s like all WWII veterans) shared his experiences with me, I knew that I needed to take the photos of WWII veterans and give testimony to these stories now! After 25 years as the Spurs' photographer, I retired to begin the project, "Before They're Gone: Portraits & Stories from World War II Veterans."

Cole was the co-pilot of Medal of Honor recipient Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle during the famous Doolittle Raid on Tokyo in April, 1942. It was the U.S.'s response to the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. The plan was to bomb the Japanese mainland and subsequently land in an airfield in China to fuel up. Cole said, "After bombing Tokyo, we did make it to China, but were short of our destination and had to bail out. Worst day in the Army Air Corps—April 18, 1942 when I had to bail out over China in the dark. Best day in the Army Air Corps—April 18, 1942 when my parachute opened."

How many WWII veterans have you interviewed and photographed? What is your goal for the project?

To date I have photographed 139 World War II veterans across Texas and the U.S. including:

- Edgar Harrell, Clarksville, TN, Sgt. USMC, 1943-1946. Harrell is the last living Marine survivor from the sinking of the USS Indianapolis, which was struck by two Japanese torpedoes in 1945. The first torpedo hit 40 feet in front of Harrell, cutting off the bow of the ship. The ship sank in 12 minutes and no distress signal was issued. Of the 1,196 men on board, 879 perished. Harrell and the other survivors spent four days in the Pacific Ocean starving, dehydrated and fending off shark attacks. They were rescued when a passing plane spotted them. Harrell received seven battle stars.

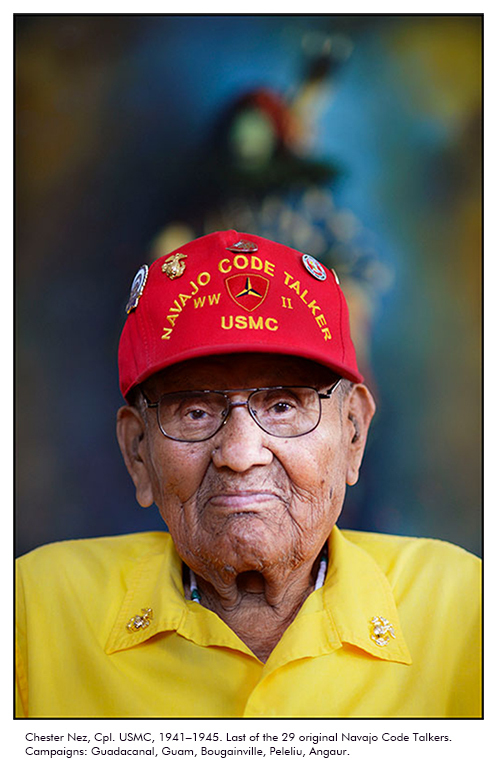

- Chester Nez, Albuquerque, NM, Cpl. USMC, 1941-1945. He was the last of the 29 original Navajo Code Talkers in the 382nd Marine Platoon. The group developed a secret communication code based on the Navajo language, which hindered Japanese forces and helped the U.S. win WWII in the Pacific. He fought in the Guadalcanal, Guam, Bougainville, Peleliu and Angaur campaigns.

- Yoshio Nakamura, Whittier, CA, SSgt. U.S. Army, 1944-1946. Nakamura and his family were taken from their home and forced to live in Japanese internment camps. Shortly thereafter, Nakamura enlisted in the Army in 1944. He joined the 442nd Regimental Combat team, comprised largely of Japanese-American troops. It was one of the most decorated units in U.S. military history. Nakamura fought in France and Italy against the Nazis and was awarded a Bronze Star.

- Ken Potts, Provo, UT, BM1C, U.S. Navy, 1939-1945. He is one of two living survivors of the USS Arizona sinking on December 7, 1941 at Pearl Harbor. Potts, a crane operator on the USS Arizona, was ashore when the harbor was attacked. He climbed aboard the burning ship to help rescue shipmates. Potts boarded a transport boat minutes before the ship exploded and sank. Over 1,100 sailors and Marines on the USS Arizona were killed during the attack.

Eventually, I would like to photograph between 175-200 veterans. I still have several I want to contact. The coronavirus lockdown in 2020 interrupted all travel, but I am anxious to get started shooting again. I have been exhibiting the photographs throughout Texas and even nationally. I am also working on a book with the help of Roger Christian & Company.

How do the veterans feel about this project? Do they welcome you with open arms or are many of them reserved? Are their families involved in the project to some extent?

The veterans love it and want to participate. With many being in Texas, it helps that I was the Spurs photographer for 25 years. Also, that I was a Marine. I have a 3-page poster that I send to public exhibition spaces and to veterans who I would like to photograph. The veterans see the posters and realize this is a serious project. As a thank-you, I give each veteran a 7x11 image framed to 14x17 in cherry wood, along with copies for their children. The families are not involved but are most appreciative. I share with them that not everyone was in harm's way, but everyone had their life changed.

My own father fought in the South Pacific with the Army. Perhaps he said it best when I asked him, "Dad, tell me about WWII in 25 words or less." He glared at me and said, "It was four years of just trying to stay alive."

What is your process for interviewing and photographing?

I begin by getting to know each veteran and making them feel comfortable. We visit for up to two hours and I record the session. I try to get some information about their early years and how they got into the service. Then I ask where they served, what branch of service, unit, general job description and duties. I also like to find out what they've done after being discharged. The process is free-flow; I just see where the talk takes me. I ask most people what their worst day and best day was in the military.

My editor, Tamara Trudeau, transcribes the recordings and writes a 600+ word bio that hangs with each photo.

Not only is the project very challenging, it is interesting and worthwhile. I have always shot fast, figuring out what I want to do, then doing it. This process worked well for the Spurs as they are not going to wait around for a photographer to figure things out. All the WWII veterans I photograph are in their 90s with a few in their 100s. They don't like to dawdle.

I decided early on that, for the most part, I wanted to take environmental photographs. Some veterans have their office complete with awards and remembrances of one of the most important events of their lives. For others, their office of remembrances is a distant memory. They have been downsizing their living quarters and now call one room in an assisted living center home. I try to record the sparseness of their lives. I walked into one veteran's/friend's room and said, "How are you?" He replied, "Just waiting around to die."

I started out primarily using a Chimera Octa 2 Beauty Dish to pop in a little light, but as the project matured, I relegated that light to my car. Occasionally I use a flash bounced off a wall to drop a little light into deep shadows. I have six low wattage daylight bulbs to put in desk lamps in the scene. I am using the Nikon D850 camera with the following lenses: 20mm f/1.8, 28mm f/1.8, 58mm f/1.4 and 105mm f/2. I really like the shallow depth of field.

Do you have a favorite person that you met? A favorite story?

There are so many, but here's a few:

- Johanna Butt, 1st Lieutenant Army Nurse Corps, 1943-1946. In January 1945 she treated wounded from Patton's Third Army at the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium. She said, "One time General Patton came into the operating room tent. I told him to get out. He wasn't supposed to be in there." Butt thought she was going to get in trouble for that. However, to her relief, Patton turned to her and said, "Lieutenant, I commend you for the work that you're doing so well." Butt said, "We saluted and he walked out."

- Fred Harvey, Private First Class USMC, 1942-1945, Iwo Jima veteran. He was awarded the Silver Star and Purple Heart. Fred was seriously wounded on Iwo Jima. Several days later, he woke up on a hospital ship in a very dark room. There were cots with 100 men in there. The doctor who operated on him walked by and Fred got his attention. They took him to another room and Fred asked what room he was in. The doctor leaned down and with tears in his eyes said, 'Fred, we call that God's waiting room. There's nothing else we can do for you. It's up to God whether you live or die.'

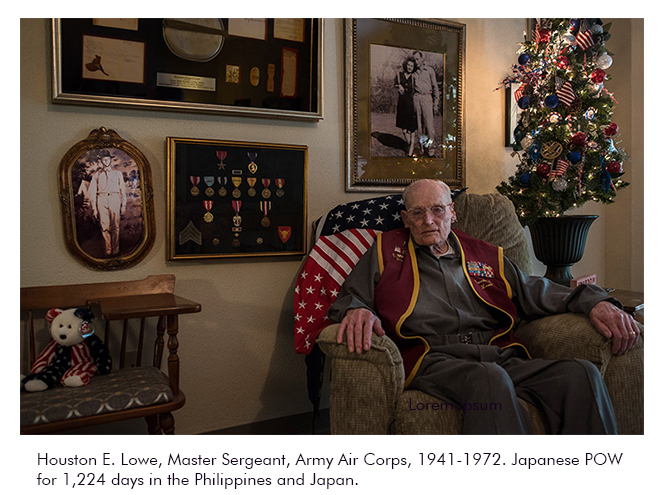

- Houston E. Lowe, Master Sergeant Army Air Corps, 1941-1972. Lowe was captured on May 6, 1942 when American troops surrendered to the Japanese following the Battle of Corregidor in the Philippines. Lowe was a Japanese POW for 1,224 days in the Philippines and Japan, surviving multiple prison camps and the Japanese freighter Noto Maru, known as the "Hell Ship." Read the book about his life, 868 the Sharecropper's Son by his daughter, Tina Farrell, Ed.D. That was the number the Japanese gave him—POW 868. Simply stunning book.

- Hershel "Woody" Williams said, "My best and most frightening day in the Marine Corps was October 5, 1945—the day the President put the Medal of Honor around my neck." Woody is the last living Medal of Honor recipient from the Battle of Iwo Jima. He said, "When my company was taken off the front line a week and a half later (after landing on the beach), all but 17 of the 279 men who had hit the beach with me had been killed or wounded."

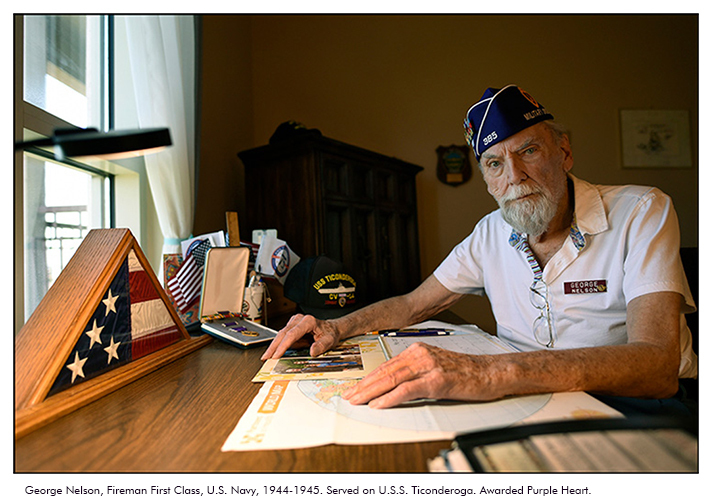

- George Nelson, Fireman First Class U.S. Navy, 1944-1945. He served on USS Ticonderoga and received a Purple Heart. George has one of the more interesting stories. "My dad joined the Navy and told my mom that under no circumstances should I be allowed to join. I finally convinced her, and she co-signed for me. I joined the Navy and was stationed aboard the USS Ticonderoga. I'd write letters to Dad [pretending] like I was in high school, running cross country and how my marks were bad. Mom would put the letters in another envelope and send them to Dad." Nelson explained that a kamikaze plane hit the ship and exploded in the middle of the flight deck. "When I came to, my leg was on my face. I ended up in Guadalcanal at a major hospital. The guy in the next bed looked too old to be in the service. The guys that were coming in were from Iwo Jima. I asked this guy and he said, 'I'm a Seabee.' I said, 'My Dad's a Seabee, 71st Battalion.' He said they were a half mile down the road. I hadn't seen my dad in almost three years.The doctors went and got my dad, and he had one comment, 'What the hell are you doing here?' He never knew I was in the Navy."

What do you admire about these WWII veterans? Is there a defining trait or commonality about their lives?

It's their unyielding perseverance and humility. They were ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Dick Cole said, "We were just doing our jobs."

The more you talk, listen, read and learn, you ask yourself, "How the hell did they do that?" Their stories stay with you. It is very emotional for me.

Simply put, this is the project of a lifetime. I've never had more fun nor worked harder, and I love it.

D. Clarke Evans is a graduate of Brooks Institute of Photography who served six years in the Marine Corps Reserve from 1964-1970 and was honorably discharged as a Sergeant. He also has a Master of Arts degree in Museum Science. Clarke was the team photographer for the San Antonio Spurs from 1989-2015. He served as president of the Texas Photographic Society from 1993-2013. Today Clarke devotes his time to two personal projects, "Semper Fidelis: Portraits & Stories of US Marines," and "Before They're Gone: Portraits & Stories of World War II Veterans." To read more about his work, go to www.dclarkeevans.com.