Blog Author David Gremp

Notes on the Charles A. Swedlund Daguerreotype Collection

One of the beautiful things about photographs is their relative permanence. From the very beginning, image stability—the ability to “fix” the image—was of paramount importance to those many scientists and alchemists pursuing a process that would create a mirror image of individuals and the world that would be lasting . . . for generations. And, the first successful and popular process, the daguerreotype, has proven to be just that. Examples that remain today, over 180 years after they were created, still retain the identical, untainted image that was produced in the camera, processed and placed into its protective case, which was required to prevent scratching on the delicate image plate.

Daguerreotypes are a sight to behold: elusively holographic in a strange sense and yet infinitely detailed and tangibly objectified by their thick, durable, and often beautiful encasements that resemble a small book which you must open in order to view the image inside. Which is then further protected behind a sheet of glass and, more often than not, a thin brass decorative plate to "frame" the image. They are truly one-of-a-kind gems that tell their own uniquely individual stories of a moment, or instant in history.

I was fortunate to have studied photography with Charles Swedlund during the mid-70s. In addition to being a gifted, creative photographer and passionate educator, he had accumulated a massive private collection of virtually every conceived photographic process and shared it freely with us all. An amazing learning tool for any student of the medium! I’ve had the good fortune of remaining in touch with him throughout my life and recently had the pleasure of working with him and his collection, most specifically with his daguerreotypes, of which he has acquired more than 1,100 examples over the past 60+ years. While most of them could be classified as “generic” classic studio portraits of common individuals, most of which are in pristine condition, he also has numerous “groupings” of specific types, such as “freaks” and post mortems.

In preparation for a presentation of his collection to The Daguerreian Society’s annual conference and show in New York City this past October, Swedlund began organizing and studying his holdings from unique perspectives. He analyzed the different ornamental treatments given to the design and materials used in making the cases, the exterior embellishments, the interior fabrics and even dismantling the cases to find such hidden surprises as locks of hair, four-leaf clovers, poems and ads for the photo studio that produced them. He also explored the various means of adding color and ornamentation to the original monochromatic image.

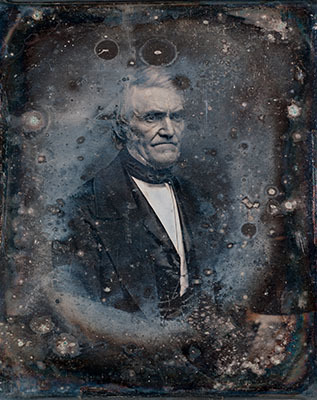

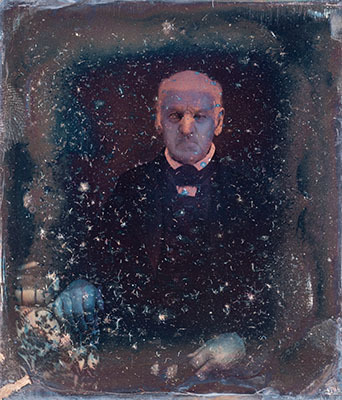

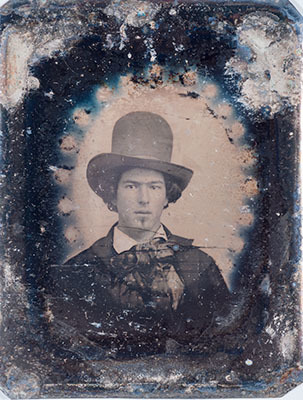

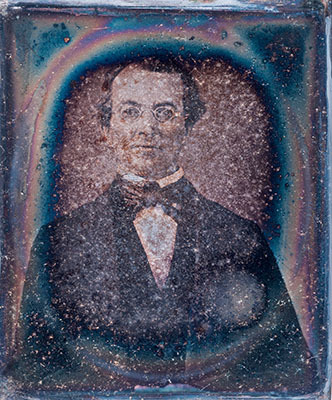

One “grouping” that was extremely fascinating, to me at least, was a collection of several dozen image plates that had been removed from their cases by an antique dealer and sold as empty “frames” for contemporary photos. The plates had been tossed into a drawer without any protection from the air or physical abuse. Swedlund purchased the entire drawerful—for a song, I’m sure. Who in their right mind would want a bunch of beat up, scratched, scuffed, oxidized and strangely discolored metal plates with barely a recognizable face, right?

Well, when looked at today in the group’s entirety, they resemble something alien to our preconceived notions of simple studio portraits of common, everyday “Earthlings.” Instead, they look as though they’ve traveled through much more than time, gone through a more rigorous and dangerous journey and have come out on the other side with a few scars, scares and, in some cases, metaphysical or other-worldly experiences. They have indeed had a life of their own, separate from the people depicted. Alchemy?

Swedlund has titled this group “Forgotten.” His wife Frances suggested the name. “The people in the images,” he claims, “were ‘forgotten’ when their kin/relatives sold or auctioned them. They were also ‘forgotten’ when the antique dealer placed little value on them and put them in a drawer. Well, I have not ‘forgotten’ them . . . and hope to give these ‘forgotten’ people some duly deserved respect.”

Studying Swedlund’s entire collection leaves one saddened by their anonymity and the fact that they are no longer a part of their subjects’ family archives. (How many families still have a daguerreotype likeness of an ancestor from the mid-1800s? My guess is not many, which is strange when you consider the millions that were produced over a 20-year period in America alone.). Fortunately, they are in the hands of someone who not only enjoys and appreciates them and their flaws, but also respects their unique individuality . . . warts and all.

For more information on the Charles A. Swedlund Daguerreotype Collection, visit stephendaitergallery.com, where examples will be on display in Chicago throughout the month of January 2016. A dedicated website for the entire collection will be available soon. Several publications on his collection, including Forgotten, are also available through Anna Press, 319 East Poplar Street, Cobden, Illinois 62920.